Development of the Plough – The Rotherham Plough to Now

By David Selin

In the first two articles of this series, we traced the journey of the plough from its prehistoric beginnings—simple wooden tools used by Mesolithic and Neolithic communities—to the heavy iron ploughs of the Roman, Saxon, and Viking periods. Each stage reflected broader changes in society, technology, and land use. This final article explores the dramatic advances in plough design from the 18th century onward.

In the 18th century, plough design shifted from slow ox teams with heavy ploughs to efficient two-horse teams with lighter ploughs. This change took place from 1730 and took several years to become widespread.

Joseph Foljambe of Eastwood, guided by Walter Blythe, invented the iron mouldboard and landslide for the plough. He patented it in November 1730, and it is commonly known as the Rotherham Plough. Although not the first iron plough, it was the first to achieve commercial success due to its innovative design and lighter weight. It remained in use in Britain until tractors were developed.

Traditional ploughs had rectangular frames that created significant friction. The Rotherham plough, with a triangular frame, reduced friction and was lighter and stronger. It allowed the ploughshare to align with the mouldboard, making it easier to manage, suitable for all soil types, and requiring only two horses to pull. The swing plough, named for lacking a depth wheel, was wooden but had iron fittings, a coulter, and an iron-plated mouldboard and share. This design was more efficient, light, and economical.

Joseph Foljambe’s factory was the first to mass-produce ploughs, which started being used outside of Rotherham in the 1760s.

James Small, a wagon-maker from Doncaster, established a factory in Scotland and, through mathematics and science, improved the plough’s mouldboard for better furrow turning. His unpatented design was widely replicated and enhanced by local craftsmen for efficiency based on soil conditions.

The Rotherham plough was not effective in heavy clay areas, leading local plough-wrights to modify it until new iron ploughs emerged in the nineteenth century. These early iron ploughs were based on the Rotherham design or Small’s adaptation.

As large firms such as Ransome’s emerged, they incorporated new materials and reached broader markets.

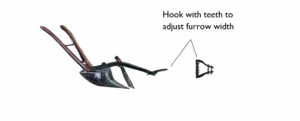

The plough shown above is among the various ploughs exhibited at Denny Abbey Farmland Museum. It is known as a digger plough, and was produced in production line quantities during its time, and made entirely of steel.

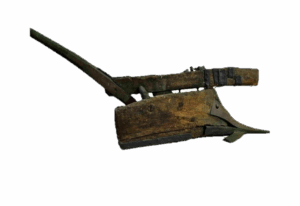

The plough shown below is known as the Barrington Plough, named after the village, where it was found. This plough belongs to an earlier period of manufacture. It includes a heavy-duty digging end. The main beam, stilts, and mouldboard are made of large wooden parts. The share is cast iron, and the base of the mouldboard is protected by an iron plate. The coulter is missing.

Today’s ploughs are highly specialised machines, often part of tractor attachments. They come in various forms—reversible ploughs, disc ploughs, and even ploughs designed to minimise soil erosion.

From hand-carved ards to precision-engineered tractor ploughs, the development of the plough mirrors the evolution of agriculture itself. The Rotherham Plough and its successors revolutionised farming by making cultivation faster, lighter, and more adaptable. Each innovation—from Small’s scientific improvements to the mass production of steel ploughs by firms like Ransome’s—built on centuries of trial, error, and local adaptation. Today’s ploughs may look vastly different from their early ancestors, but the core idea remains unchanged: turning soil to sow new life. In following the story of the plough, we trace not just the history of a tool, but the growth of civilisation itself.