The Development of the Plough in Britain – Stone Age to Iron Age

By David Selin

This article is the first in a three-part series exploring the roots of British agriculture through the lens of one quietly remarkable tool: the plough. Often overlooked, the plough has appeared throughout history as both a practical implement and a symbol of human progress. We start our story in the Mesolithic period.

The Mesolithic Britons adhered to a diverse diet comprising both flora and fauna. Hunting was crucial for their sustenance, with local wildlife serving as significant food sources. They hunted red and roe deer, pigs, horses, wolves, and wild aurochs, the predecessors of domesticated cattle. The aurochs, being large and formidable creatures, necessitated considerable expertise and collaborative effort for a successful hunt. Additionally, the gathering of indigenous plants contributed essential nutrients and variety to their diet. Nuts and berries, which were easily accessible and nutritious, formed staple foods. Knowledge of edible, medicinal, and toxic plants was passed down through generations and became a fundamental aspect of their cultural heritage.

Fishing was equally crucial to their livelihood, as Britain’s rivers, lakes, and coastal areas were abundant in fish. The development of effective fishing tools and techniques was essential for the community’s sustenance.

Circa 4500 BC, significant changes occurred with the arrival of Neolithic immigrants. These newcomers introduced agricultural knowledge and practices, profoundly transforming food production methods. They brought cereals, sheep, goats, and domesticated cattle from the continent, ushering in a new era in Britain’s history.

Farming provided more stable and predictable food sources, allowing for permanent settlements and growing population centres. Domesticated animals not only provided meat but also milk, wool, and labour, boosting the capabilities and resilience of Neolithic communities.

Farming did not completely replace the old ways. Instead, hunting, fishing, and gathering continued to be important, especially where farming was not as feasible.

Evidence of early forest clearance found across Britain suggests farming began around 5000 BC before Neolithic immigrants arrived. Dry conditions before 6000 BC led to natural fire clearings in forests, which might have helped early animal and plant husbandry by concentrating desirable species. Mesolithic farming involved the simple fostering of local species.

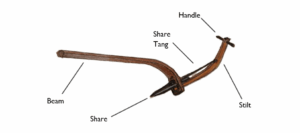

The above sketch illustrates a typical early ploughing device, made from a branch or bough of a tree, which scratched the soil surface. Working best on sandy Mediterranean-type soils, they would have been limited to areas that were easily worked.

Significant advancements came in the 4th Millennium BC with the invention of the Ard, a primitive plough that broke the soil without turning a furrow. Also known as Scratch Ploughs, they were historically pulled by oxen, camels, or even elephants. During the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, these ploughs were refined by adding bronze and then iron plates to protect the wooden shear points from wear.

Developed by the Sumerians or Ancient Egyptians, this innovation boosted productivity and led to labour division in complex societies. It spread rapidly across Europe, China, and Great Britain. Early wooden ploughs had a hook design for soil penetration with depths of 15-20 cm, requiring multiple passes to clear vegetation.

The shift from warm, dry climate to wetter Atlantic conditions led to increased bog and peat formation. The Neolithic agricultural transition (4000-3000 BC) coincided with this change, bringing advances in stone tools. By 2000 BC, Stonehenge was erected, and British agriculture flourished in fertile regions.

The development of a permanent field system can be traced back to the Iron Age. The landscape underwent a gradual transformation as agricultural practices and landholding patterns evolved. The emphasis transitioned from constructions indicative of a dominant ruling class, such as monuments and burial chambers, to fortified hilltop structures designed for the communal defence of enduringly cultivated fields. This trend reached its peak on the brink of the Roman invasion, with the construction of hill forts in the north and west and large-scale settlements fortified by banks and ditches in the southeast.

Areas designated for ploughing were marked by ditches, earth banks, or stone walls. Boundaries were sometimes identified using round barrows. Fields, typically irregular squares around one acre in size, were cultivated in a regular cycle of crops and fallow periods through cross-ploughing with the ard. Tools used during the Iron Age included spades, hoes, and small sickles.

From the foraging lifestyles of Mesolithic Britons to the organised agriculture of the Iron Age, the plough emerged as a quiet but powerful agent of change. Evolving from simple wooden scratch tools to more robust, metal-reinforced ards, it mirrored the growing complexity of British society. As communities settled and fields expanded, the plough not only reshaped the landscape but also symbolised humanity’s deepening relationship with the land—a relationship that laid the foundations for the agricultural systems still recognisable today.